Arriving in Addis Ababa the feel is completely unlike the East African countries of Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda. In Ethiopia the mix of varying ethnicities presents a pot pourri of facial characteristics - diversity on display, reflecting the country's geographical location at the confluence of different religious and cultural worlds. This may surprise Lonely Planet, which goes on about how tough it is being a

faranji (foreigner) in the country, but I found it refreshing to be, relatively, ignored compared to the incessant attention of being white in Rwanda. (Not one single shout of

faranji or 'you' did I hear, whereas there were many cries of

muzungu on the way back home from Kigali airport to Kibungo.)

|

| A Gondar castle |

Ethiopia is a huge country with the second biggest population in Africa, at about 83 million, after Nigeria. Our first guide Kiprom ('you saved us'* in Amharic) said that whites were considered just another tribe, albeit a rich one, to be incorporated into the national melting pot. As the only country in Africa that had never been colonised (note that the Italians only 'occupied' the country from 1935 to 1941), the Ethiopian people, he stated, had greater self-assurance when dealing with outsiders. Correct or not, there are certainly plenty of

faranji around with burgeoning NGO and tourism industries. Trade liberalisation has led to foreign investors planting hotels like the ubiquitous barley. Half completed edifices are a feature of the landscape, as elsewhere in the world where free market policies encourage a go/stop cycle of ready credit followed by frequent collapse. I was assured, however, that many of the buildings were just 'resting' waiting for the dry season to fully arrive before work continued.

|

| Street in Gondar |

European tours are proliferating with Italians, French and Germans at the forefront. Germans are the guides' favourites, apparently, because they don't question the itinerary and are all present and waiting outside the buses at the appointed departure times. (I don't know if they leave their towels to keep a special seat on the bus!). Some Italians, French and Spanish are the complete opposite, with an individualistic and instinctive distrust of the guides' judgment and authority. " Why can't be leave 15 minutes later and go down that bumpy road instead of this bitumen one?" More examples of truth in stereotyping it would seem.

|

| Solomon and Sheba making hay!! |

Ethiopians are immensely proud of their history and who can blame them. Bipedal Lucy (locally known as Dinknesh or 'wonderful'), at 3.2 million years of age, is still considered, I believe, the oldest and most complete hominid ever found. My doubt is simply because almost every science section of the Guardian Weekly seems to present some startling new evidence with the potential to change the whole equation. Lucy, by the way, was discovered in 1974 in a dried up lake bed in the north east of the country and her reconstruction is nestled in Addis Ababa's National Museum where she looks very sweet.

|

| Lucy |

However, it is in Ethiopia's religious history that most pride resides. Indiana Jones shouldn't have bothered searching. Orthodox Christians, the majority of the population, believe that Our Lady Mary of Zion church in Axum in the north of the country holds the original Ark of the Covenant that Moses carried with the Israelites during the Exodus. Legend has it that Emperor Menelik 1, the son of the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon, brought the Ark from Jerusalem to Axum in about 950 BC. There he settled and established one of the world's longest known, uninterrupted monarchical dynasties - nearly 3000 years and 225 generations - which only ended with the dethroning of the Lion of Judah, Emperor Haile Selassie, in 1974 by the military Derg. (Wise King Solomon was a busy man because, according to the Bible, he had 700 wives and 300 concubines!)

|

| Haile Selassie's tomb |

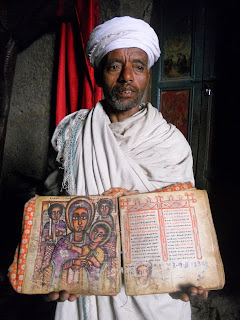

Every Orthodox Church has a replica of the tablet with the Ten Commandants in its inner sanctuary or 'holy of holies' that lay people are not allowed to see. Very frustrating. I really wanted to open the curtain for a quick peek but was worried about joining Harrison Ford in the snake pit. You need to learn Ge'ez, the ancient classical language, from which Amharic is derived, to become an Orthodox priest and have a chance of touching the sacred, covered icon.

|

| Priest with 900 year old book in daily use |

Large numbers of Ethiopians want to be priests and deacons, the preceding step. Neither is a paid position but in a society where struggling on the land with the other 85% agrarian population is the major alternative, a position in the clergy has high status and, frequently, practitioner supplied food. That is how the many monks and nuns get by - with food donations left outside the monasteries although others make a living selling artefacts, like prayer shawls, baskets and religious symbols, to passing tourists. We climbed up to one of the magnificent rock-hewn churches at Lalibela on mule-back (mine was called Molla!) and I got Kiprom to ask a young nun what had made her join the order. Secular life was full of lies, arguments and an obsession with money in which she wanted to play no part. And no, her parents did not know where she was. Gradually, according to the norm, she would retreat further and further from the outside world and its exacting demands but was free to leave the order at a later date if it no longer suited her. The longer she stayed, of course, the harder that would be.

|

| Priest with cross |

It struck me that Ethiopia is a society far more deeply imbued with the Christian religion than, even, Rwanda where, for the most part, Monday to Saturday is God-free. Ethiopian Orthodox churches, on the other hand, seem to sound off at top loudspeaker volume at all hours of the day and night with particular emphasis on the fasting days (no meat eaten) of Wednesday and Friday and with a midnight kick off on Saturday/Sunday. It's important to know the proximity of the local churches for Saturday night hotel bookings as we found to our cost in the castle town of Gondar despite the wearing of super strength earplugs. One foreign tourist, said Kiprom, practically broke down his hotel door one night telling him to get that Muslim to shut up. When K explained that it wasn't Islamic and that there was nothing he could do about it, the tourist refused to believe him insisting he knew the sound of a mosque. Some

muezzins (who call Muslims to prayer) are better sounding than others but having lived in different Islamic societies, I can attest that the call of the mosque is regular, relatively short and often beautiful in marked contrast to the incessant and repetitive day and night dirge emanating from the Orthodox churches. And when I see you, I'll tell you what I really think!

|

| Ride that hoss (actually mule) |

Ethiopian Orthodoxy believes in the literal truth of both the old and new testaments simply seeing the latter as an upgrade of the former. Where Lucy and evolution, so proudly displayed in the museum, sit in this context is not clear but the religion appears to absorb contradictions easily. (So what's new?) Angels and saints abound as the church considers that it would have been impossible for Jesus to have performed all the miracles himself and must have had help. Church tableaux are an assortment of biblical and esoteric references none more puzzling than the significance of St George and his slaying of the dragon. He crops up everywhere, next to the Holy Trinity, to the left and right of Mary, King Solomon or the Queen of Sheba or below the wise men. He even has the nicest rock-hewn church in Lalibela named after him.

|

| St George's rock-hewn church at Lalibela |

* Kiprom was born on Ethiopian New Year's Day - 1 September 1982 - when the troops of communist regime leader Colonel Mengistu were going around killing dissidents in his village. The occupants of the houses on the street front were shot but Kiprom kept quiet as he was born behind the protection of a row of eucalyptus trees. Go Aussie!